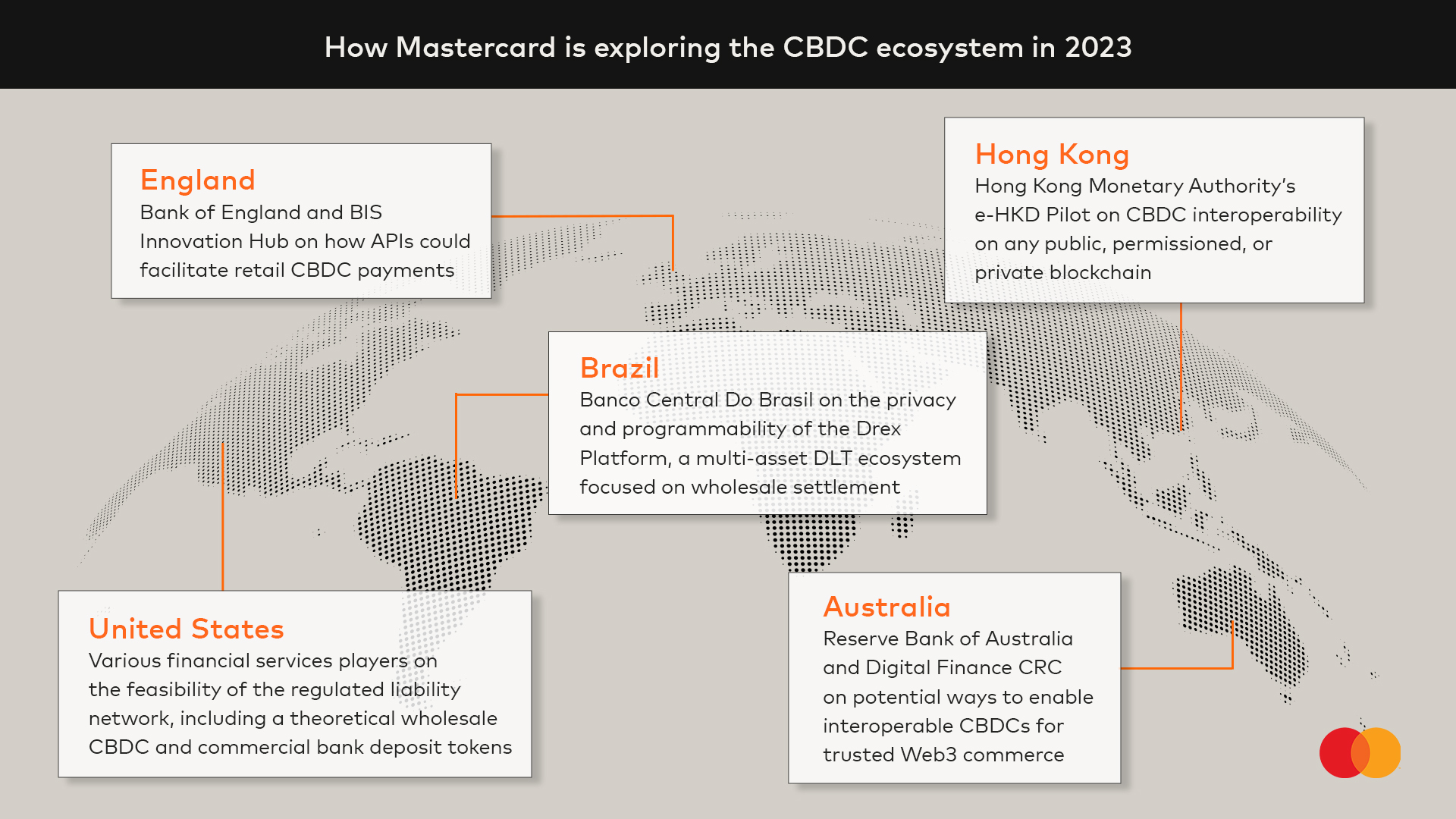

Source: Mastercard

Central banks have been exploring ways to issue their own digital currencies for years. Yet their efforts haven’t captured the public’s attention — for better or, more recently, for worse — like cryptocurrencies have. But central bank digital currencies, or CBDCs — essentially a digital version of fiat currency backed by a government and therefore far less speculative than crypto — are gaining momentum, with the potential to have an even bigger impact on our everyday lives.

Central banks around the world are experimenting with issuing these digital currencies to complement traditional payments, both the physical version in your wallet and the online version in your banking app. In fact, 93% of central banks are engaged in some form of work on CBDCs, and four retail CBDCs are already in full live circulation, according to the Bank for International Settlements.

But there are many questions that central banks need to consider, says Jesse McWaters, who leads global regulatory advocacy at Mastercard. This includes the role of the private sector in CBDC issuance, security, privacy and interoperability — such as how a CBDC works with other commonly used payment mechanisms, what specific challenges CBDCs would solve and whether they’re even the right tool for the job.

To bring a greater understanding of the benefits and limitations of CBDCs and how to implement them in a way that is safe, seamless and useful, Mastercard is convening a group of leading blockchain technology and payment service providers to join its new CBDC Partner Program. It’s designed to foster collaboration with key players in the space so they can drive innovation and efficiencies, says Raj Dhamodharan, head of digital assets and blockchain at Mastercard.

The inaugural set of partners includes CBDC platform Ripple, blockchain and Web3 software company Consensys, multi-CBDC and tokenized assets solution provider Fluency, digital identity technology provider Idemia, digital identity consultant Consult Hyperion, security technology group Giesecke+Devrient and digital asset operations platform Fireblocks.

Their efforts include Fluency’s work to build interoperability among different CBDCs, Consult Hyperion’s work with central banks and payment processors to define their CBDC requirements and Ripple’s launch of an inaugural government-issued national stablecoin in collaboration with the Republic of Palau, in addition to work on four CBDC pilots.

“We believe in payment choice and that interoperability across the different ways of making payments is an essential component of a flourishing economy,” Dhamodharan says. “As we look ahead toward a digitally driven future, it will be essential that the value held as a CBDC is as easy to use as other forms of money.”

CBDC program partner Giesecke+Devrient, based in Germany, has a legacy in public currency that dates back 170 years, when it first started printing banknotes. Today the company specializes in safeguarding both physical and digital assets. It works with central banks to roll out digital currencies, offering its CBDC solution called G+D Filia, which can enable secure offline payments. That feature is important both for ensuring as many people as possible can use CBDCs and ensuring you can access your money even amid connectivity problems or power failures. Filia can be used for online and offline payments using a variety of wallet types and IoT devices.

“What we’ve seen is that cash is still there, and that won’t change, but there is emerging demand for a public digital currency,” says Sebastian Baierle, manager of strategic partnerships for CBDC at G+D. “And the intentions vary from country to country.”

Baierle says the Bank of Ghana — which is partnering with G+D on its CBDC pilot — wants to use CBDCs to bring more of its citizens into the formal financial economy. By contrast, the Swedish central bank might be more concerned that the rapid shift away from cash in that country is reducing consumers’ access to a form of money directly backed by the central bank, something it is committed to preserving, McWaters says.

“As we look ahead towards a digitally driven future, it will be essential that the value held as a CBDC is as easy to use as other forms of money.” – Raj Dhamodharan

As the technology continues to mature, there’s still plenty for this partnership to study and consider. For one thing, CBDCs have yet to gain wide acceptance. While BIS expects as many as 24 central bank digital currencies to be circulating by decade’s end, more than two-thirds of central banks say they’re unlikely, in the near term, to issue a digital currency people can use for everyday purchases.

This stems partly from the complex issues involved, says Varun Paul, who was most recently head of the Bank of England’s fintech hub and now oversees CBDC and market infrastructure for Fireblocks.

For example, central banks must determine how to strike the right balance between privacy and transparency, to prevent illicit activities while preserving an individual’s right to privacy.

“Privacy is extremely important to users. It’s really the No. 1 topic,” says Jerome Ajdenbaum, who leads the digital currencies business for Idemia, citing a recent European Central Bank survey on the digital euro. It’s vital to demonstrate to the user that their privacy is protected, “not just that we promise” to do so, he adds.

Idemia develops cryptographic techniques for offline payments to ensure privacy for individuals, while still maintaining enough oversight to prevent fraud. The company has partnered with the Bank of England on exactly this issue, working to understand the right level of privacy for its CBDC project.

Another conundrum is getting people to use the new digital currency. In the few countries that have formally adopted CBDCs, some people have been reluctant to adopt a form of money they’re not familiar with, Fireblocks’ Paul notes.

Hesitancy may have increased in the wake of last year’s “crypto winter,” with scandals threatening the trust that the digital ecosystem needs to evolve and thrive. Paul says that recent high-profile collapses actually strengthen the case for CBDCs, which (like regular currency and government bonds) are fully backed by a central bank and government.

For CBDCs to succeed in the years ahead will also require central banks to build trust through improved communication. “I’d argue,” Paul says, “that there’s a huge amount to be done to explain to the public what this thing is, why it should be used and when it should be used.”

CBDCs shouldn’t be adopted in a vacuum, and the work of the Mastercard CBDC Partner Program will help central banks understand how to develop a CBDC that adds something new and valuable to the economy, McWaters says.

“By assembling the strengths, deep expertise and different capabilities of these partners, we can drive innovation in the central banking community and along the CBDC value chain as the space continues to evolve,” Dhamodharan says.

Implemented poorly, a CBDC could create disruptions in the established payment system and crowd out private sector investment. Citing U.S. Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome Powell on the potential for a digital dollar, McWaters adds, “It’s more important to get it right than to be first.”