1. Purpose of this paper

This paper is intended to provide a high-level framework of personal data types and functional uses of personal data within the ecosystem of a payments system.

Its objective is to facilitate discussions on privacy in the context of a digital Pound by enabling consistent terminology.

Some functional elements described in this document are explicitly out of the scope of the exploratory design work being conducted by the Bank of England. However, they remain areas of concern for those wary of the privacy implications of a digital Pound and are therefore worth describing.

- Section 3 describes functions needed in or otherwise likely to be associated with a payments system.

- Section 4 categorises the types of data processed in a payments system.

- Section 5 describes how the data categories set out in section 4 are used by the functions set out in section 3.

- Section 6 provides a high level overview of existing relevant data privacy laws.

- Section 7 provides a set of design considerations with respect to privacy, which will be expounded upon in later papers.

We welcome feedback on this paper and are committed to refining and enhancing it in future iterations. Please send any thoughts or comments via our feedback form.

2. Context

Data privacy is a matter of the highest order in the design of any payments infrastructure. Our rights to privacy are protected in law, as summarised in section 6 below. When physical notes and coins are exchanged from hand to hand, the transaction is essentially anonymous and there is no digital audit trail created about the transaction. Electronic payments bring convenience and efficiency, however due to the digital audit trail, some level of privacy is traded for the functional utility.

Today’s electronic payment systems are effectively messaging systems recording the movement of liabilities from one financial institution to another. Settlement – the actual movement of money – happens at a separate time, between the financial institutions’ accounts at the Bank of England. Reconciliation processes that link the payment to the related transaction are separate and sometimes complex and expensive.

The Bank of England is currently exploring a potential digital Pound, a new form of legal tender with potentially profound implications for financial systems. As well as enabling people and businesses to hold fiat currency directly in their own name and pay one another directly with it, the technological infrastructure would also allow for the linking of data, exceeding the data recorded today, to the payment transaction. What data is recorded and accessible by which parties has implications for the personal privacy of people using digital Pounds, and is therefore a hugely important aspect of this design.

Before considering privacy requirements, it is important to understand the functions required [or otherwise likely to be present] within a payments system and the personal data that is needed to be created and shared between those functions. This paper aims to set out a simple analysis of what those functions are, what the generic data types are and what the data needs are of each function to be able to fulfil its purpose. This will then set the foundation to explore and appropriately design a payments platform that sufficiently protects privacy where required, whilst also supporting, if not enhancing, compliance with anti-money laundering, anti-terrorist financing and anti-fraud requirements.

The detailed design and use cases for a digital Pound remain in the exploratory phase. The framework proposed in this paper is derived from consideration of current payment systems. It might be applied to proposed future use cases in order to consider data sharing requirements and privacy principles or to provide more detailed analysis for specific contexts, for example international payments, B2C transactions, large value payments, etc.

3. Functions needed for national payment systems

Unlike notes and coins, when digital Pounds are exchanged they will be automatically linked with data that has the potential to be shared – in whole or part – with multiple persons.

Various different persons may have legitimate interests in being able to access data within the system – for example, to protect society from money launderers and financial crime; or to better manage their customer relationships or create new services, with benefits for users.

Set out below are a set of functions that a Payer and Payee may wish to be provided under a digital Pound, or which wider society and government may need to be fulfilled. In section 3 below we categorise the data types that are needed to fulfil these functions and on what basis it is obtained.

Payer and Payee

The Payer sends digital Pounds to the Payee. One or other may be acting on behalf of a legal entity, i.e. the transaction could be B2C rather than C2C. In order to make the payment, the Payer must have sufficient data to be able to identify the Payee within the system. In a shop or restaurant, the Payee may simply present a card terminal which the Payer assumes is connected to the correct account.

The Payee may need some identity data about the Payer, for example that the Payer is an adult or in order to be able to evidence ‘source of funds’. These needs are driven by laws and regulations designed to achieve various public policy objectives.

Other needs are driven by convenience and efficiency rather than regulation. These needs are met by commercial services. For example, the payment might be provided through a retailer’s app so that it is automatically associated with loyalty discounts. Such services might be a benefit provided by a PIP’s Digital Wallet.

Commercial Services

Under a digital Pound the Bank of England has defined that Payers and Payees will use the services of a ‘Payments Interface Provider’ (PIP) who will provide each of them with a Digital Wallet in some form through which the digital Pounds will be transacted.

In the diagram above PIPs are shown in their own box. However, they are categorised as commercial services and it is assumed that a market of Digital Wallet providers will offer different features for different types of customer. A Digital Wallet service may be cross subsidised by other forms of commercial service, whether financial or otherwise. For example, it would be easy to imagine mobile phone hardware manufacturers or telecommunications companies providing a Digital Wallet.

For this analysis we are considering a commercial service as one that uses the personal data generated from the core function of making and receiving payments. The uses may be for various purposes:

- providing the services inherent in the operation of the system (making / receiving payments);

- testing / improving the services offered by the PIP;

- managing the wider relationship between the PIP and its customer, for example, marketing;

- etc.

When referring to current payments systems we refer to a ‘Payments Provider’ as the equivalent of a PIP.

Digital Pound Infrastructures

The central ledger, payment processing systems, et al required for the digital Pound are described under this category. The design process is in progress but the Bank of England has stated that neither the Government nor the Bank will have access to users’ personal data and that privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) might support privacy while assisting PIPs in complying with legal and regulatory obligations.

In addition to the core operational functions, we have defined three key systemic functional needs for data within payment systems.

- Provision of Financial Stability and Infrastructure

In order to preserve trust in a digital Pound, and more broadly the UK financial system, there will need to be confidence that transactions through the system are being monitored in order to identify potential causes of systemic failure.

Typically, systemic failures are caused by a ‘run on a [commercial] bank’ – but the Bank of England will hold liability so customers will not have such fears.

There may be other types of infrastructure that need to be monitored to prevent operational failures. It is unlikely that any personal data will need to be processed.

- Implementation of Monetary Policy

The introduction of a digital Pound presents opportunities for enhanced, timely data acquisition that can significantly aid in the execution of monetary policy and overall economic management.

While the Bank of England’s consultation papers do not indicate any functional requirements with regard to monetary policy, this capability could potentially be supported by the central ledger of the Bank of England’s digital Pound.

However, this doesn’t necessitate recording individual personal or business accounts on the central ledger. Instead, an aggregated view of customer or market segment data should be sufficient.

- Prevention of Criminal-Activity

The infrastructure of a digital Pound must safeguard against various forms of criminal behaviour:

- Money Laundering: To prevent the laundering of digital Pounds through ‘clean’ accounts where legitimate transactions occur, ongoing monitoring and analysis of transaction sources are required.

- Terrorist Financing: A similar challenge to money laundering, the payments systems should not be used to enable terrorist activities to be funded.

- Sanctioned Users: The digital Pound must not be accessible to individuals under sanctions. This necessitates robust identity verification processes for those creating and managing Digital Wallets and access to the respective PEP and other clearly defined source datastores.

- Fraudulent Minting: It seems unlikely that digital Pounds will be minted fraudulently unless an insider is involved. Anticipated safeguards in the technical design should prevent such activities. However, should any breach occur, operational oversight is expected to detect it. Furthermore the minting should be carried out in an airtight manner, totally isolated from any external or internal systems, with a detailed process to move minted pounds from and to the mint after minting or for destruction.

Collection of taxes, payment of welfare

HMRC can request information from financial institutions for individuals that they suspect of evading taxes. There are proposals in Parliament for a change in law to allow the DWP to access bank accounts for claimants to “detect signs of fraud or error”.

For small businesses, a number of services exist to automate the declaration and payment of taxes. No such services currently exist for personal taxes but employers by default calculate the ‘Pay As You Earn’ (PAYE) taxes and pay them directly to HMRC, by-passing the employee.

During the decade following the 2007/8 financial crisis, there was much criticism of the effectiveness of Quantitative Easing (QE) to resuscitate the economy or do more than protect the banking sector. The Bank of England has dismissed the digital Pound as a means of introduction of ‘helicopter money’, a Universal Basic Income (UBI) or other novel forms of policy. However, such possibilities are likely to exist via a digital Pound infrastructure and so the privacy implications should be considered.

4. Data Categorisation

This section proposes a categorisation for payments related data.

A. Transaction Data

Data that is generated by a payments provider with details supplied by the Payer (push payments) or Payee (pull payments).

- Payee and Payer Data:

- Account numbers and names are essential for identifying the parties involved in the transaction.

- Transaction Details:

- Including the amount, date, and time is crucial as these details provide a timestamp and quantify the transaction, which is necessary for record-keeping and verification.

- Reference and Reason for Payment:

- Reference data such as invoice number is critical for connecting the payment to specific goods, services, or obligations, enhancing the traceability of transactions.

- The reason for the payment (e.g., mortgage repayment) adds a layer of context that can be useful for accounting and regulatory purposes.

- Location Data:

- Capturing the location of the payer at the time of authentication and the location of the payee when receiving the payment can play a significant role in fraud detection and regulatory compliance, especially when cross-border transactions are involved.

- Transaction ID/Cryptokey:

- A unique identifier for each transaction can aid in tracking and can be crucial for resolving disputes or investigating potential fraud.

- Authentication Method:

- Detailing the method of authentication used (e.g., biometric, two-factor authentication) can provide additional security insights and compliance data.

B. Static Data

Data that is not typically shared in a payment transaction but can be derived from it or requested from a payments provider if needed.

C. Regulatory Data

Customer data that must be verified and maintained by the payment provider.

D. Authentication Data

Data that is used to authenticate a user’s identity and account access rights and initiate transactions.

Authentication typically involves verifying something the user knows, something the user has, or something the user is. Here’s how each element is typically managed:

- Biometrics (Something the user is): most often a facial image, perhaps extracted from an official identity document, used to verify the user’s identity as part of the onboarding process. Biometrics may also be used for online account login and transaction authentication. Typically, in this context, the biometrics are stored on the user’s device.

- PIN and Passwords (Something the user knows): These are secret codes or phrases that users know and are used to verify their identity. Both PINs and passwords are stored and maintained by the banking institution, allowing users to change them as needed for security purposes.

- Account Knowledge (Something the user knows): This term typically refers to data that the user should know about their account, which can be used for secondary verification processes, like security questions posed during a password reset. Examples include previous transaction details, account details or contact data. This data aids in confirming the user’s identity, especially when primary authentication methods are compromised.

E. Derived Data

Insights that are drawn from payments data is described here as ‘derived data’. Some examples are provided below.

- Relationships between Parties: Identifying relationships, such as employer-employee dynamics, could be sensitive and may require explicit consent before collection and use.

- Spending Patterns and Frequency: Analysing how frequently transactions are made and identifying spending behaviours can provide insights for customer relationship management. However, this practice must be transparent, and customers should be informed of such monitoring.

- Transaction ‘Normality’ and Monitoring: Assessing the ‘normality’ of transactions to detect anomalies requires careful handling to ensure it does not infringe on privacy rights.

However it is an important and justifiable practice for fraud prevention, detection and compliance purposes but should be explicitly documented, on a need to know basis, in the internal operations and risk management guidelines of the payment services provider.

- Account Balance: Monitoring and recording account balances for internal records need to be done with the user’s knowledge and consent.

It is particularly critical, in this area, for payment service providers to ensure that they have identified a clear lawful basis for their processing of users’ personal data. The appropriate lawful basis will vary between different use cases.

F. Aggregated Data

Aggregated data is compiled by organisations managing payment systems to analyse payment trends and contribute to macro-economic insights. However, this data must be consolidated and obfuscated to protect individual privacy. Consent will not normally be necessary for use of anonymised data. GDPR-compliant consents cannot in any case be obtained through general terms and conditions.

5. Use of Data

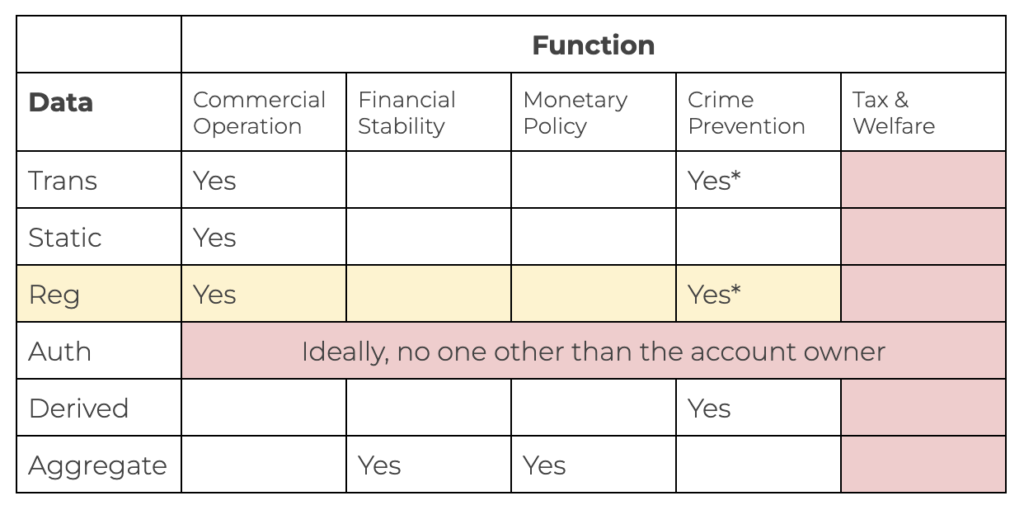

Below, we consider the uses of the data categories defined in section 4 by each of the functions defined in section 3.

Verifying the Payee’s account

Push Payments (Payer initiated Transfers): Payers face notable challenges in confirming the identity of account holders when making “push” payments, or account transfers. As these transactions become more prevalent, the Payments Systems Regulator has issued a Special Directive requiring payers to be notified if there is a discrepancy between the entered details and the registered name of the account beneficiary.

Face-To-Face Payments: In settings like shops and restaurants, the use of mobile payment terminals typically limits the information displayed to the payer to just the payment amount. This approach is generally acceptable as the transaction is conducted face-to-face and is accompanied by a paper receipt, providing physical evidence of the transaction.

Pull Payments (Payer Authorised Recurring Account Debits): For “pull” payments, such as Direct Debits, there tend to be more reliable verification of the payee’s identity and established procedures for addressing disputes. These types of payments are often used for regular, agreed-upon transactions like utility bills where there are clear, pre-approved mechanisms for recourse.

Payee

The risks associated with receiving money incorrectly are naturally a lower concern than the risk of paying money in error. However, the payee will need to be able to reconcile received payments and be able to evidence receipt in some circumstances. The payment reference is likely to be used for this purpose rather than the account name of the payer.

Commercial Services including Payment Providers

Payment Providers generate the data associated with their customer and the associated payments made and received. They use this data to fulfil the commercial operations to their customer, according to the agreed Terms and Conditions, associated privacy notices and, where appropriate and required (e.g. in the case of use of customer data for direct marketing purposes), consents or opt-outs.

They may also share data with third parties, again in accordance with the agreed Terms and Conditions and associated privacy notices and consents or opt-outs.

These operations must be delivered in compliance with existing laws and regulations.

Digital Pound Infrastructure

The design of the Digital Pound infrastructure must cater to the requirements of other functional areas. The specific technical details regarding where and how personal and business data are processed, stored, and accessed should be determined based on the operational needs of these various functions.

Provision of Financial Stability with the Digital Pound

Financial instability can arise from numerous sources, often due to innovative but destabilising uses of financial systems. The key to anticipating such instabilities lies in identifying new and unusual patterns of behaviour from a macro and micro economic point of view. For this function, access to transaction-level personal data is unlikely to be necessary. Instead, data aggregated from individual transactions should be adequate to support efforts in maintaining financial stability. How and when data is aggregated is critical from a privacy perspective.

Implementation of Monetary Policy with the Digital Pound

The implementation of monetary policy using the Digital Pound infrastructure likely does not require access to individual personal or business data. Instead, aggregated data that references specific customer or market segments should suffice. This approach ensures that the necessary information for monetary policy can be gathered without compromising the privacy of individual users or the confidentiality of business information.

Prevention of Criminal Activity

Money laundering

Detecting money laundering requires a strategic analysis of end-to-end transaction flows and the relationships among account controllers. Employing advanced big data analytics to spot unusual transaction patterns allows for the effective monitoring of systemic risks without the need for invasive scrutiny of individual accounts. Such monitoring practices should be rigorously justified to prevent undue privacy intrusions and ensure the protection of individual rights.

Sanctioned Users

The prevention of the digital Pound’s use by sanctioned individuals involves the implementation of sophisticated automated systems for digital identity verification at the time of onboarding, complemented by continuous, automated monitoring of sanctions lists, politically exposed persons (PEP), and other relevant adverse lists.

Fraudulent Minting

The risk of fraudulently minting digital Pounds is anticipated to be addressed by robust minting processes at the Bank of England, advanced technology deployment, and strong cryptographic solutions.

However, vulnerabilities in cases of offline transactions due to systemic failures or natural disaster and potential double-spending still pose a risk, especially in implementations of the digital Pound infrastructure that may not adhere to the strictest and most advanced off-line processing standards.

Potential issues like double-spending or fraudulent transactions within the digital Pound system are typically identified once offline transaction processing — related to specific digital Pounds, regions, or transactions — is complete. These issues come to light when the offline wallets restart their synchronisation and validation processes with the online system.

Therefore, it is anticipated that the technology provider selected to support the digital Pound infrastructure will need to demonstrate a thoroughly comprehensive and rigorously stress-tested approach to managing offline processing and ensuring a smooth transition back to online operations once connectivity is re-established.

The techniques used to reconcile offline transactions and wallets with the online system must include stringent privacy protections. These safeguards should be embedded through careful technical design and deliberate strategic decisions made during the initial design phase of the digital Pound infrastructure. Such measures ensure the integrity and security of the digital Pound while also protecting user privacy.

Terrorist Financing

This is addressed in a similar manner to money laundering.

Collection of taxes, payment of welfare

The efficiency of the systems used for collecting taxes and paying welfare could in principle be greatly improved for both the benefit of government operations and the convenience of citizens. However, again, there would be significant privacy implications of how this is done. It remains, perhaps, one of the most significant suspicions of opponents of a digital Pound, that, once a digital Pound has entered ‘normal’ use, such a system might be introduced.

Categories of data need for each function

6. Data Privacy Law

In considering personal data processing within payments systems we have considered existing UK privacy law, summarised below.

There are three main sources of (relevant) UK data privacy law:

- At the overarching level, there is the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA), implementing the European Convention on Human Rights. In particular, article 8: respect for private and family life constrains the UK’s freedom to legislate in a way that disproportionately infringes privacy.

(EU law establishes an overarching privacy principle more directly, through the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, article 8 – right to the protection of personal data. This does not apply in UK law but, in practice, the HRA is likely to have a similar effect.) - The article 8 principle is implemented into UK law through the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR), the post-Brexit equivalent to the EU GDPR. The UK GDPR is supplemented by the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA). The UK GDPR and DPA regulate the processing of personal data both within and outside the financial services sector.

- There is also specific regulation of the processing of personal data collected for AML / CTF / similar purposes – the UK Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds (Information on the Payer) Regulations 2017 (AML Regs), which, as well as requiring data to be collected and retained for these purposes, also:

- (regulation 41) prohibit processing of these data except for AML / CTF / similar purposes, as specifically permitted by law or with data subject consent; and

- (regulation 40) require AML / CTF / similar records to be deleted after five years, with limited exceptions.

These regulations, which pre-date Brexit, implement requirements of the EU anti-money-laundering regime.

Data Privacy Principles:

There are seven founding principles underpinning the UK GDPR:

- Lawfulness, fairness and transparency: personal data must be processed in a manner that is fair, lawful and transparent. All processing must have a lawful basis (AML processing, for example, is typically carried out based on the “required by law” or, in limited cases, the “legitimate interests” lawful basis – the latter requiring a careful balance to be struck between the interest in fighting financial crime and the privacy of the data subjects).

There must be transparency about the processing of personal data, ensuring that individuals are informed about how their personal data will be used. This is typically achieved through the use of privacy notices and policies. - Purpose Limitation: personal data must be collected for specified, legitimate purposes, made explicit to the data subject, and cannot be further processed in a way that is not compatible with these initial purposes. This GDPR principle is reinforced by AML Reg 41 and remains an essential requirement for data sharing between organisations.

- Data Minimisation: the processing of personal data must be restricted to only what is necessary for the purpose and the data must be relevant and adequate for this purpose.

- Accuracy: every attempt must be made to process accurate and up to date personal data, ensuring that mechanisms exist to allow the correction or erasure of inaccurate personal data, where applicable.

- Storage Limitation: personal data must be deleted when it is no longer required for the purposes for which it was collected. In the context of a payments system and digital Pound, this would entail storing data in a manner that does not enable the identification of an individual for longer than necessary.

- Integrity & Confidentiality: often referred to as the ‘security principle’, personal data must be handled securely to guard against unauthorised or unlawful processing, accidental loss, destruction, or damage.

- Accountability: organisations must be able to demonstrate compliance with the privacy laws.

Other Considerations stemming from privacy laws:

- Privacy By Design: the GDPR makes it a legal requirement to ‘bake in’ data protection from the design phase, right through the lifecycle of a project.

- Special Categories of Data: there are tight restrictions on the processing of sensitive personal data, including data relating to actual or alleged criminal offences, ethnic origin, political affiliation, religious beliefs or sexual orientation. These data elements are often disclosed during AML screening checks.

- Data Subject Rights: various rights are afforded to data subjects, including the right of access to their personal data, correction, erasure, portability, objection to its processing, etc. These rights must be integrated into the design of new models, products or features.

7. Design considerations

Below are a set of design considerations to balance the need for privacy and security with the efficiency and transparency required in a modern financial system, ensuring that the digital Pound is both user-friendly and trustworthy.

Known network participants

All entities participating in the network – such as banks, businesses, and users – should be authenticated and identifiable in appropriate circumstances. This ensures that transactions are conducted by verified parties to reduce fraud and malicious network behaviour, which enhances security and trust in the system while allowing the network to be monitored and managed effectively. However, while participants are known, their specific transaction details can be anonymised to protect individual privacy.

Privacy preserving

Privacy-preserving mechanisms are integrated into the digital Pound to ensure that individual transaction details and personal data are protected from unauthorised access. This involves using cryptographic techniques, such as zero-knowledge proofs or secure multi-party computation, to allow transaction validation without revealing sensitive information. The goal is to maintain user security and confidentiality while ensuring compliance with regulatory standards (i.e. KYC/KYB, AML, etc.)

Persistency and immutability

Transactions in a digital Pound system are recorded in a way that makes them permanent and unalterable. This is often achieved using blockchain or distributed ledger technology (DLT), which ensures that once a transaction is recorded, it cannot be changed or deleted. Persistency and immutability provide a reliable and tamper-proof record of all transactions, enhancing transparency, trust and auditability.

Whilst accounting rules necessitate a permanent ledger to be maintained, GDPR allows an individual the ‘right to be forgotten’. These requirements must be reconciled with one another in the design of a payments system to maintain immutability of records while adhering to privacy requirements.

Open Standards based

The digital Pound system is built on open standards to promote interoperability, flexibility, and innovation. Open standards ensure that the digital Pound can integrate with various financial systems, platforms, and technologies. This encourages wider adoption and enables third-party developers to create complementary applications and services, fostering a more inclusive financial ecosystem and competition.

Privacy by design

Privacy by design means that privacy considerations are integrated into the digital Pound architecture and technical design choice from the outset rather than being added later as an afterthought. This approach ensures that all aspects of the digital Pound — from its architecture to its operational procedures — are designed to protect user privacy. It involves proactive measures, such as data minimization, user consent (where appropriate), and strong encryption, to safeguard personal data throughout the entire transaction process.

Centrally managed standards with decentralised operations

The digital Pound system is governed by the Bank of England, which sets policies, ensures regulatory compliance, and oversees the system’s integrity. However, the operational aspects of the digital Pound can be decentralised, distributing transaction processing and verification across multiple nodes or financial institutions. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of central governance, such as regulatory oversight and monetary control, while benefiting from the resilience, efficiency, and security of decentralised operations.

Solution techniques

In the development of this paper, a number of techniques were discussed to protect privacy and security and thereby maintain public trust:

- Data Privacy Frameworks: Develop comprehensive data privacy frameworks that align with international standards, such as the EU and UK GDPR. These frameworks should define how personal data is collected, stored, processed, shared and ultimately deleted or anonymised, ensuring that users’ privacy rights are protected.

- Minimising Data Collection: Implement data minimization principles by collecting only the essential information required for the functioning of the digital Pound. This approach reduces the risk of data breaches and protects users’ privacy.

- Anonymity and Pseudonymity: Explore options for providing anonymity or pseudonymity in Digital Pound transactions. While full anonymity may conflict with anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorism financing (CTF) regulations, pseudonymous transactions can strike a balance by protecting user privacy while allowing for regulatory compliance.

- Advanced Encryption Techniques: Use advanced encryption techniques to secure all data transmissions and storage. End-to-end encryption ensures that data is protected from unauthorised access and cyber threats.

- Regular Security Audits: Conduct regular security audits and vulnerability assessments to identify and address potential security weaknesses. Independent third-party audits provide an unbiased evaluation of the system’s security posture.

- Transparency and Accountability: Maintain transparency about data practices and security measures by regularly publishing reports and updates. Establish clear accountability mechanisms to ensure that any breaches or misuse of data are promptly addressed.

8. Conclusion

Privacy is a subject that stirs emotions and is relative rather than absolute. To formulate principles that a majority of stakeholders can endorse, a shared understanding of the underlying components is essential.

This paper serves not as a detailed exploration of privacy safeguards but as a high-level framework to facilitate such discussions using consistent terminology.

While some aspects of the framework are explicitly excluded by the Bank of England, they remain areas of concern for those wary of potential changes in policy. Thus, these topics are worth discussing.

We welcome feedback on this paper and are committed to refining and enhancing it in future iterations.

Submit your feedback

We welcome feedback on this paper and are committed to refining and enhancing it in future iterations. Please click the button below to send us any thoughts or comments you may have about the paper.