The Digital Pound Foundation (DPF) takes pleasure in responding to the Bank of England and HM Treasury’s (HMT’s) Consultation on a Digital Pound (the “Consultation”), and to the Bank of England’s accompanying Technology Working Paper on the digital pound.

The DPF’s stated remit is to advocate for and support the implementation of a well-designed digital Pound, in both publicly and privately issued forms, and a diverse, effective and competitive ecosystem for these new forms of digital money in the UK. As such, we wholeheartedly support the Bank of England’s continued exploration of a digital Pound in the form of a retail CBDC, and we appreciate the chance to share our thoughts and expertise on the subject. We would welcome the opportunity for further engagement and discussion with HMT and the Bank of England on the Consultation, and any other related consultations and discussion papers as may be relevant and appropriate.

The DPF’s members are uniquely qualified to contribute to the discussion around introduction of a CBDC, as they are all already actively involved and engaged in the development of new forms of digital money – whether as professional service and technology providers for CBDC projects, issuers of digital money, or firms whose business models depend on the existence of new forms of digital money. Our response to this Consultation is therefore informed by a collection of forward-looking viewpoints and an active envisaging of the future ecosystem of new forms of digital money and of any CBDC’s role and place within this context.

We share the Bank’s view that public access to public money is of fundamental importance to maintaining trust within the UK’s financial system. It is our view that public money also represents a fundamental expression of the relationship between the UK government and the general public. We are in agreement as well with the Bank’s consideration that a more radical shift towards greater use of private money, in the form of both existing commercial bank money as well as the emerging paradigm of tokenised deposits, tokenised e-money and other variants on privately-issued stablecoins, could result in a situation whereby some members of society are left behind or further excluded from access to the financial system, due to the focus of the private sector on more commercially advantageous customers.

Furthermore, despite the dramatic increase in usage of commercial bank money – private money – for everyday transactions over the past two decades, and the corresponding decline in cash usage, cash remains an intrinsic part of the money ecosystem, and millions of UK residents still depend on using it for many reasons. It is our view that, ultimately, public money represents the only fully accessible and inclusive form of money that we have. As physical cash use declines[1], therefore, the case for introducing a digital alternative to publicly-issued cash (whilst not necessarily supplanting cash in its entirety) grows ever stronger – as does the need for full transparency and clarity around the differences between the various new forms of digital money, the risk profiles attached to them and the need for enhanced digital inclusion.

In designing its own CBDC, the UK has an opportunity to play to its strengths – including its desired strategic objectives – and to develop a CBDC that can contribute not only to maintaining a position of global leadership, but also to lead the way in standard setting, effective regulation, sustainability and delivery of ESG objectives. As a digital-native form of public money, a retail CBDC could have significant benefits for the UK public, as well as becoming a key means of delivering more effective public policy in the transition to a digital economy. A nation’s currency is not only its store of value, unit of account and medium of exchange; when deployed strategically, it has the potential to create new economic opportunities. The introduction of a sovereign currency that is able to participate fully and actively in digital ecosystems will enable the UK to further build on its economic and social development and growth. It could act as a potential differentiator and accelerator of innovation for the UK on the global stage, by providing a vital component of the financial markets and payments infrastructure of the future.

We therefore welcome the Consultation – The digital pound: a new form of money for households and businesses? – and in particular its proposed ‘platform model’ for public-private partnership that fundamentally acknowledges the role played by public money – accessible to retail users – in maintaining confidence in the financial system, alongside the role of the private sector in the wider financial services ecosystem that underpins our economy.

We also appreciate the Bank’s recognition of the importance of public trust and confidence in the design of any CBDC system, and its proposal of a design and market structure in which, importantly, neither the Bank nor the Government will have visibility of user data, and which does not create a more intrusive system that that currently in place with respect to accounts, cards and payments today.

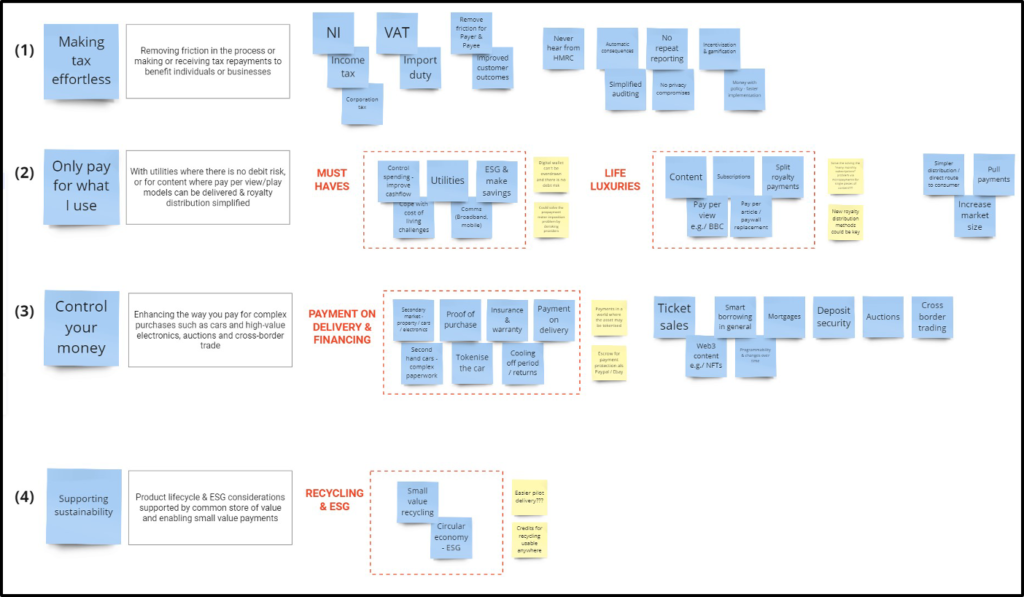

We would also strongly advocate for the Bank to encourage practical initiatives to support ongoing retail CBDC design exploration, building on the Project Rosalind work to date. This could take the form of a sandbox along the lines of the FCA Regulatory Sandbox or a competitive Proof of Concept build process along the lines of that recently carried out by the Australian central bank. In this practical vein, the DPF’s Use Case Working Group (WG) has been exploring real-world use cases for a retail digital Pound for some time and our current thinking is presented in Annex 2 below. We would welcome the opportunity to discuss these and to explore them further with the Bank at its convenience.

The DPF does however observe that the Bank, whilst progressing its exploration of a retail CBDC, has thus far remained largely silent on the topic of wholesale CBDC. We note the Bank’s reference to a private sector initiative for wholesale settlement on distributed ledger technology using central bank money via an omnibus account. But there is no reference to the extensive work being undertaken by the various Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Innovation Hubs, in conjunction with a number of central banks globally, in exploring the potential for wholesale CBDCs and their role in improved cross-border settlements as well as in enabling enhanced digitisation of financial markets and their infrastructures. This also stands at odds with jurisdictions such as Brazil, Australia and India, which all have wholesale CBDC pilots currently underway. It also stands in contrast with the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee’s observation, in its report on CBDCs, that there is a strong case to be made for the introduction and uptake of a wholesale CBDC.

As a point of clarification, throughout this Consultation response document we have referred to the Bank’s proposed digital Pound CBDC as “CBDC”, “retail CBDC”, or “digital Pound CBDC”. This is due to the fact that, for the Digital Pound Foundation, when we refer to a digital Pound we are referring to both public and privately issued versions of a digital Pound, and so wish to make clear throughout this document that we are commenting exclusively on the Bank’s proposed introduction of a central bank-issued digital Pound CBDC.

Policy Drivers for a Retail CBDC

We are aware of many industry discussions, including those amongst our own members, on the ultimate utility and use cases for a retail CBDC in the UK. We expect that these will continue to progress over the coming months and years, and indeed the DPF’s own Use Case Working Group is exploring these potential applications. Furthermore, the DPF is actively embarking on a programme of activity to highlight the foundational role of a UK retail CBDC in enabling enhanced policy delivery across a number of areas of the UK economy and Government focus, including but not limited to better delivery of benefits, enabling digital trade (an area ripe for development following the introduction of the Electronic Trade Documents Bill), and improved revenue collection capabilities. We would welcome the opportunity to discuss these topics with HMT, and in understanding how we can shape our work to support HMT’s wide policy agenda for a UK CBDC, should this be of interest.

That said, we see the following as key policy drivers for the introduction of a retail CBDC in the UK:

- Central bank money as the anchor of monetary and financial stability – we are very much in agreement with the Bank’s assertions around the role played by both retail and wholesale central bank money, as well as robust regulation and supervision, in maintaining trust in the financial and monetary system. As transactional use of cash – the only other form of publicly accessible central bank money available – continues to decline, it makes sense to maintain public access to public money through the introduction of a digital-native form of central bank-issued money both for transactional purposes and as a store of wealth. We note as well the Bank’s observation that the role played by a future CBDC in supporting the uniformity of money is not necessarily dependent on high public uptake of the CBDC; it is sufficient that it exists, and is accessible, and that other privately-issued forms of the Pound sterling can be converted to it on demand and at par.

- A vector for interoperability between new forms of digital money – The DPF envisages a future in which multiple different forms of money – both public and private, and both those currently in use as well as new forms of digital money – coexist. Each has the potential to fill a different niche in the ecosystem and to provide enhanced consumer and business choices, arising from their different characteristics, the technical functionality that they offer, the nature of their issuers and the risk (both real and perceived) attached to them as a consequence of all of these taken together.

In order for our vision of a diverse, competitive and effective ecosystem for new forms of digital money to become a reality, seamless interoperability, convertibility, and – above all else – preservation of the singleness of a digital Pound in all its varied formats, will be required. Just as bank deposits can today be converted into cash, or e-money into bank deposits, the future evolution of money and payments will require equally seamless, trusted and invisible conversion between cash, bank deposits, e-money and new forms of public and private digital money.

We are supportive of the Bank’s vision (Box E), of the role that can be played by a CBDC in a mixed payments economy, in coexisting with, and complementing, systemically important stablecoins, tokenised deposits and tokenised e-money, and other new forms of digital money, and also providing a form of interoperability and rails between existing payment infrastructures and future digital platforms.

- Platform for innovation – Sir Jon Cunliffe, in many of his speeches as well as most notably in his oral evidence given to the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee[2] has often noted the potential for a UK CBDC to provide a platform for innovation in ways that might, at present, not be entirely foreseeable – much in the same way that the role of the smartphone in everyday life and the extent to which it has transformed the way in which people interact with each other, with services and with businesses, could not have been foreseen at the time the first iPhone came to market.

There has also been a growing recognition of the wider benefits associated with CBDCs beyond their use as payments instruments. This includes opportunities for innovation and competition arising from a digital-native central bank-issued money offering programmable functionality. Nevertheless, the adoption of any CBDC is heavily dependent not only on its technical features but also on the way in which characteristics such as privacy, resilience, security, and consumer protection are built into its design and that of its accompanying infrastructure.

A UK CBDC, if implemented, with its potential as a platform for innovation as a driver of design choices, can form a vital piece of national infrastructure underpinning not only the UK’s transition to a digital economy, but also the continued attractiveness of its financial services and FinTech sectors relative to other jurisdictions. The existence of a CBDC that can be used, for example, to underpin settlement of digital asset transactions, or can have smart contracts embedded, is in itself an attractive feature and draw for innovative firms to locate themselves in the UK.

- National security and monetary sovereignty – At present, the US dollar is either used directly for settlement or indirectly as an intermediary currency for settlement of 88% of all FX transactions globally. Along with the degree of dollarisation (partial or full) inherent in a number of jurisdictions, and the use by most central banks of the US dollar as a reserve currency, this reliance on the US dollar enables the US to exercise a significant degree of extraterritorial economic and political power in terms of sanctions enforcement and influence. Recent events in Ukraine, and the West’s response in cutting Russia off from the financial system, have further spurred interest from many jurisdictions in exploring CBDCs for cross-border payments as a means of insulating themselves from similar situations. This in turn has incentivised the US to pick up the pace on its own CBDC explorations, particularly when it comes to wholesale CBDC which can be used for cross-border settlement (albeit with considerable negative views being expressed with respect to the introduction of a retail CBDC, and two States, Texas and Florida, passing legislation to prevent the use of any future federal-issued CBDC within their territory).

There is certainly an advantage to being a first mover, or an early adopter, with respect to CBDC. A jurisdiction that has implemented a well-designed CBDC with design features that appeal to a broad user base, and relatively open access to users outside its own borders, may find its currency in greater demand. Some jurisdictions may start to mandate payments to and from service providers in their own CBDC. If, for example, China were to do this with respect to its “Belt and Road” initiative, the consequences for uptake of its Digital Yuan CBDC and payments system – outside its own borders – would be significant, and could have knock-on effects in local economies, effectively leading to a reserve currency status in certain parts of the world. A CBDC, therefore, can have geopolitical impacts, and impacts on the monetary sovereignty of nations.

Initially, at least, CBDCs represented a reaction from central banks to proposed new forms of privately-issued digital money, most notably Meta’s (formerly Facebook’s) Diem (formerly Libra). Even as the case for CBDCs has further broadened, privately-issued stablecoins continue to pose a potential challenge for the monetary sovereignty of some central banks. A US dollar-denominated stablecoin that is made available to consumers and businesses beyond the US could quickly begin to supplant the use of the local currency, particularly in times of currency volatility or political uncertainty (a situation which can arise even in developed economies such as the UK, as the events of 2022 have shown). For the impacted central bank, this could in turn lead to a creeping dollarisation effect and corresponding loss of monetary sovereignty domestically alongside loss of confidence on the world stage – a wholly undesirable situation, by any standard (as the Bank itself notes on p28 of the Consultation).

From an international perspective, it is becoming increasingly apparent that CBDC is a necessity for any nation-state wishing to preserve its sovereignty in determining fiscal and monetary policy in a world that will be increasingly fuelled by both privately operated, decentralised digital currencies and other types of digital assets. The exercise of sovereign power by a nation is closely linked to its ability to leverage and exert influence through its currency and how that currency is perceived and used at both domestic and international levels.

- Continued competitiveness of the UK’s currency on the global stage – in a world in which 68% of central banks consider it likely that they will issue a retail CBDC in the short or medium term (p34), it is increasingly likely that the form and functionality offered by a currency will become a competitive differentiator for a jurisdiction like the UK.

The UK, at present, has a world-leading financial services industry, in terms of both incumbents and new entrants/challengers, as well as FinTechs. Its regulatory environment is extremely conducive to innovation, and its common law system and ability to adapt to change at pace are the envy of many jurisdictions. However, the UK is in danger of falling behind many of its global trading partners and competitors when it comes to the transformational capabilities of new technologies, including CBDC, that are increasingly capable of influencing the balance of power in trade and finance. Whilst no technology implementation can be completely future-proof, we also observe that many of the jurisdictions that are actively experimenting with, piloting or implementing CBDCs are doing so on advanced and frontier technologies, presenting them with potential opportunities to exploit competitive advantages with respect to the capabilities and functionalities offered by their currencies and payments infrastructure.

The Bank of England has been the centre of finance for over 300 years and a well-designed digital Pound will enable the UK to maintain its position as a leading global financial centre at the cutting edge of innovation. The introduction of a UK CBDC will have impacts and repercussions far beyond payments infrastructure. It will provide a platform for innovation that can support the UK’s transition to a digital economy. It is a fundamental infrastructure that can underpin the delivery of numerous policy objectives. Taking a forward-looking approach to policy and technology decisions will help deliver a design that is more future-proof and ultimately enable the UK to maintain a leading edge in an increasingly competitive global financial markets and FinTech landscape.

Additional Observations

In addition to our responses to the Consultation questions, and to the Annexes that we have attached, we would like to make the following observations:

Legal basis for CBDC issuance

There remain outstanding questions as to the legal characteristics and functionality of a digital Pound CBDC, as well as more granular regulatory considerations surrounding its issuances.

- The legal features

Firstly, the Consultation has not fully considered whether the CBDC design should be token-based (equivalent to currency) or account-based (functioning as a settlement mechanism). The ramifications of the former characteristic, regarding the dual position of digital and private/public money, requires high-level policy consideration.

Secondly, the Consultation notes that micropayments could be a driver of end-user engagement (p34). Further consideration is therefore needed as to how such fractionalisation would be reflected in the legal ownership of the CBDC.

Thirdly, the Consultation notes that programmability, delivered by PIPs, would improve functionality for end-users – for example, through the ability to implement smart contracts (p32). It is not entirely clear whether such programmability is expected to be a feature offered within the currency as an API, for example, that can be used by PIPs, or whether the implication is that PIPs could offer services involving programmable payments around a CBDC. In the case of the former, further consideration would be required as to the Bank of England’s authority for issuing programmable currency, and regulatory oversight with respect to PIP delivery of that programmability.

The Consultation also makes clear that the Bank is not proposing to introduce a CBDC that enables government or central bank-initiated programmability (p79). It is unclear as to how such a restriction might be enforced, in the long term, if the CBDC is designed to be programmable by some ecosystem participants and actors and not by others, and the extent to which such a design might erode the basis for trust amongst users should also be considered.

We would also welcome additional clarity as to how and at what level PIP-implemented programmability could exist in a system based on a single account held in a centralised ledger by the Bank of England. Would programmability in this scenario be implemented at the wallet level, and not at the base central ledger level? Would this potentially make it easier to circumvent, and potentially less useful from a functional perspective?

- Interoperability

The Consultation states that uniformity and trust in the safety, interchangeability and equal value of all forms of money are the bedrock of the UK’s economy (p25). Following on from this, it goes on to assert the role of interoperability as a key feature of the CBDC, in preserving the uniformity of money and in bolstering UK systemic resilience (p51). The DPF recommends that further consideration should be undertaken of the legal frameworks necessary to facilitate the interoperability of the CBDC with other forms of money (such as bank deposits, cash, e-money and stablecoins), as well as interoperability with existing domestic and cross-border payment platforms.

As the Consultation also states, a recent survey of central banks showed that 68% consider it likely or possible that they will issue a retail CBDC in the short or medium term (p34). We would strongly recommend that the Bank and HMT develop their consideration of the legal and diplomatic processes necessary to facilitate interoperability between retail CBDCs denominated in different currencies. The Bank may also wish to consider the types of forum/policy discussions that may be necessary to aid the development of a consistent framework between different jurisdictions.

For a UK CBDC to have maximum utility for people and businesses, it will need the ability to support cross-border transactions, and to maintain the UK’s currency as a competitive one on the global stage, offering an attractive platform and infrastructure for the financial services community. If lacking in the ability to support cross-border transactions, a UK CBDC may ultimately have use only within domestic UK financial services and activities, and thus put at risk the UK’s attractiveness and openness as a global financial centre. We are mindful of the explorations undertaken by the various BIS Innovation Hubs as well as private sector actors around how such interoperability bridges might be implemented in practice across different jurisdictions and their CBDCs, and would encourage the Bank to monitor these developments closely and to potentially explore the prospect of multiple solutions to these challenges, including potential private-sector solutions.

- Payment Systems

The Consultation states that settlement finality for any transactions must be a feature of the CBDC (p51). Integration with or amendment of the UK Settlement Finality Regulations should therefore be an area of consideration with respect to legal prerequisites to the introduction of a CBDC. The Consultation also notes that a retail CBDC could improve domestic payment system resilience by acting as an entirely new payment system that could operate outside of existing ones for CBDC-to-CBDC payments only (p36). There is also an implication that in effect the Bank will become a payment system operator. If this is the case, then further consideration is required as to the role (if any) that PIPs will play alongside the Bank in operating a new payment system, and therefore the extent to which they would be integrated into (a potentially extended version of) the Payment Services Regulation and be regulated by the Payment Systems Regulator, or whether it would be more appropriate for them to be subject to new system rules.

Additional Considerations around Regulation of PIPs

The Consultation envisages that PIPs will serve as the main interface between end-users and the CBDC, and states (p61) that PIPs participating in the retail CBDC system would be held to at least the same standards relating to financial crime as those to which regulated payment services providers (PSPs) are held today, including to prevent money laundering, terrorist financing, and fraud. This is a good starting point, although more detail is required as PIPs may operate very differently from current PSPs (e.g. authorised electronic money and payment institutions). We concur that PIPs are unlikely to require extensive prudential regulation merely by virtue of their activity in the course of providing CBDC services, given that they will not be in possession of end users’ CBDC funds, like Payment Imitation Service Providers in the Open Banking ecosystem, which therefore limits the counterparty or credit risk to customers. Nevertheless, there are some issues surrounding data privacy and due diligence which warrant further consideration.

Firstly, the Consultation states in Part D.1 that PIPs will be responsible for Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) checks, and compliance with Combating the Financing of Terrorism requirements. Further consideration is needed as to how this responsibility will be reflected in any PIP-specific regulatory framework, or whether PIPs would fall under the scope of the existing Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds (Information on the Payer) Regulations 2017, and the Funds Transfer Regulation 2015.

As the Consultation recognises, such regulation serves as a source of friction between national payment systems. Therefore, the PIP regulatory regime should balance the need to prevent financial crime with the goal of facilitating more efficient cross-border payments to the UK’s economic advantage.

Secondly, we appreciate that a retail CBDC will not be anonymous, as gathering customers’ personal data is necessary for KYC / AML and ongoing financial crime prevention, detection and enforcement activities. PIP compliance with existing data protection laws can help to protect users’ privacy. However, there are additional levels of security and confidentiality which can be built into the CBDC and which should be considered further.

We also note that the Consultation proposal for PIPs to access personal data and their ability to use it for different processing purposes is stricter than UK GDPR and Data Protection Act provisions. Various legal bases available under the GDPR are excluded including the potential to process personal data where the firm has a ‘legitimate interest’ in the processing, on the condition that there are no overriding negative impacts on the rights and interests of the individual. This prevents PIPs from using data for various functions which would have a low impact on privacy – for example: training models, market analysis, protecting vulnerable customers, and compliance processing.

These functions can be beneficial to society and, as such, alternative means of providing strong privacy protections should be considered such as: giving tools to customers to ‘opt out’ of certain data processing (for example, having data processing ‘on’ by default but allowing customers to turn it off) or working with the ICO and industry on specific CBDC guidance (for example, a Statutory Code under the Data Protection Act 2018). Moreover, there remain outstanding policy questions in relation to the protection of user-generated data. Given that PIPs will need to become identity holders and verifiers, they could become potential targets of cybercrime.

It is our view that, given the Consultation’s assertion that at a minimum the standards that apply to PSPs will apply to PIPs, if we follow the “same risk, same regulatory outcome” principle then the Payment Services Regulations (PSRs) represent a good starting point for all of the above considerations, and the question of whether more or less is needed, or why a different approach might be required, should be considered in light of the potential differences that might arise from unique PIP business models and their associated risk profiles. Presumably, a PIP would also be subject to the new FCA Consumer Duty rules, as well as other principles that are broadly applicable to regulated firms.

D. Consultation Response

1. Do you have comments on how trends in payments may evolve and the opportunities and risks that they may entail?

The payments landscape is already highly digitised in nature, and this is often used as an argument against the need for the introduction of new forms of digital money – and, in particular, CBDCs. Nevertheless, it is important to note that credit, debit and charge cards (and the payments services built on these) are not themselves forms of digital currency; they are mechanisms for effecting payments using digital money, with underlying credit facilities or corresponding bank transfers. Payments apps are labelled in some jurisdictions as “e-money”; they are functionally the same as cards, creating an electronic means for transferring digital money. E-money accounts are also provided by many challenger banks and offered by payment solutions providers.

The introduction of regulatory regimes for e-money and open banking has opened up a host of opportunities for innovation in payments, as has the development and widespread adoption of near field communication (NFC) and “contactless” payments. Consumers and businesses are now able to access a wide range of payment services and to transact through a variety of channels and mechanisms.

The emergence of cryptocurrencies, and in particular the distributed ledger technologies (DLT) on which they are implemented, has also driven greater exploration of and challenge of the fundamental assumptions underpinning existing money and payments infrastructures. The development of DLT-based cryptoassets that can be used for payments and cross-border settlement represents the next evolutionary stage of digital-native money and digital payments. Digital payments built on this technology deliver near-instantaneous transaction settlement combined with a high degree of transparency and traceability.

The creation of privately-issued stablecoins, in their various forms, has further spurred interest in the public sector – particularly in light of then-Facebook’s proposed introduction of then-Libra in 2019, and the impetus this gave to central banks in terms of exploring the potential benefits, challenges and opportunities of new forms of digital-native money. Whilst it is true that, at present, the primary live use case for stablecoins remains settlement on cryptocurrency exchanges, the possibility of a new non-bank-issued stablecoin emerging and rapidly gaining widespread retail usage remains real, and has been recognised in HMT’s recent consultations on cryptoassets and stablecoins.

Privately-issued stablecoins, whether they are used as a means of payment in retail transactions, a means of cross-border settlement, a means of facilitating payment on-ledger for digital assets or for enabling smart contract execution, generally create counterparty exposure to the private issuer. The creation of a large number of private stablecoins, that are themselves not necessarily interoperable, may also lead to greater market fragmentation. There are also many undesirable effects of large-scale stablecoin use from a monetary policy perspective – including the potential for public money to be moved from general circulation and onto closed, private networks, and for private companies to (inadvertently or not) manipulate currency value through large movements in the currency or assets backing the stablecoins. Stablecoins also necessarily ‘piggy-back’ on the value and acceptance of the reference fiat currency (unit of account and store of value); the only feature of money where they could differ is as a means of payment, for example by being more convenient to use. A directly digital form of public money could be more efficient.

That said, we do also recognise the positive benefits and role to be played by stablecoins and other private issuances (e.g. tokenised deposits and tokenised e-money) in the ecosystem of new forms of digital money. The DPF actively advocates for an ecosystem of new forms of digital money that is diverse, effective and competitive, and we envisage a future in which these all coexist with CBDC and existing forms of money, playing different roles and perhaps competing on the basis of accessibility, functionality and utility. There is potential value to the Bank in engaging with issuers and supporting both the Government and private sector in exploring the use cases and benefits offered by privately issued new forms of digital money (especially those that might be backed by reserves held at the Bank) alongside its ongoing work in designing and implementing a CBDC.

The use of unregulated stablecoins and cryptocurrencies for fraudulent purposes, money laundering, terrorism financing and other criminal activities has largely been addressed by the FATF, with stringent new AML and KYC requirements introduced via local regulations such as the EU’s 6th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (6AMLD). Nevertheless, there remains potential for private stablecoin providers to replace banks and payments institutions in terms of holding value and processing transactions, and the rules governing the former are not as strict in terms of conduct or prudential requirements as they are for banks. In light of these risks, many jurisdictions, including the UK, are moving swiftly to bring stablecoins into the regulatory perimeter.

There are also consumer protection concerns associated with the widespread use of stablecoins and cryptocurrencies in payments and settlements. In the UK, under the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS), deposit-holders are currently protected to a limit of £85000 should their bank fail. Similar protections apply for other regulated forms of private money, like e-money (including in tokenised form). In contrast, the future failure of a popular stablecoin, or a crash in a widely used cryptocurrency – understandably without any form of protection scheme at present given the relative lack of prudential oversight – could have a damaging impact on financial stability, with both retail customers and businesses at risk of losing their holdings in these assets.

The extent to which these privately-issued alternatives will be adopted remains to be seen. However, central banks must be open to the risk of the market moving in this direction and equip themselves with the means of replicating the utility of cryptocurrencies and private stablecoins, so that their central and independent roles in preserving trust and confidence in the financial system remain effective. The introduction of a well-designed digital Pound CBDC would provide a central bank-backed alternative digital-native form of money, that preserves consumer protections whilst also enabling the benefits associated with digital currencies and payment mechanisms associated with them.

That said, there are indeed risks associated with the introduction of a retail CBDC:

- The introduction of a CBDC could lead to outflows from commercial bank deposits into CBDC holdings, resulting in lower deposit balances being held with commercial banks and hence posing challenges to the ability of commercial banks to maintain their lending abilities and role in credit creation, all other things being equal. The Bank of England has proposed that the introduction of a CBDC be accompanied by holding limits for consumers, and that the CBDC itself would not be interest-bearing – two features which would, taken together, encourage use of the CBDC for transactional purposes as opposed to stores of value.

- We are not, however, in favour of the prolonged long-term use of limits as a means of managing this risk. As per our response to Question 7 of the Consultation, continued use of limits to disincentivise individuals from large-scale holdings of CBDC will, in our view, only serve to disincentivise financial institutions from offering genuinely competitive account rates and services, thus ultimately distorting the market and delivering sub-optimal consumer outcomes.

- Furthermore, the decision to make the CBDC non-interest-bearing, whilst aligned with the treatment of cash, may in the long term prove to be a limiting factor in the Bank’s ability to propagate monetary policy decisions through the economy at pace. A number of economists have recognised the potential value of an interest-bearing CBDC. Whilst we recognise the drivers for a CBDC that is, initially at least, non-interest-bearing, we would strongly urge the Bank to consider adoption of a design that allows for future interest rate propagation, but is initially set to 0%.

- It is often argued that CBDCs could lead to the disintermediation of commercial banks. The Bank’s proposed “platform model”, encompassing a layer of payment interface providers (PIPs) who offer services and products based on the CBDC, is aimed at mitigating this risk (although the commercial incentives for PIPs to offer these products and services are yet to be fully understood, and this may influence the uptake of institutions applying to become authorised as PIPs and the subsequent product and service offerings). Additionally, to the extent that development of a CBDC results in greater competition from non-bank providers to fill the roles traditionally played by commercial banks, consumers could benefit as well.

- Introduction of a CBDC will require financial institutions, including both banks and payments market participants, to assess the impact on all of their front-to-back technology and operational infrastructure and processes. When viewed in the context of the wider wholesale review, re-engineering, modernisation and digitisation required for a successful transition to a digital economy, this is not necessarily a negative development. Nevertheless, the challenges associated with loss of data, sunk investment costs due to CBDC making previous or planned changes redundant, and general re-engineering challenges are all challenges that must be managed.

- More significantly, Pay.UK will need to ensure that the retail payment systems (Bacs and Faster Payments / NPA) are compatible with a retail CBDC, so as to ensure interoperability between those users that wish to pay with the CBDC vs those that want to receive commercial bank money, for example.

- Public trust in a CBDC is vital, in order for successful commercial uptake. Public trust can be negatively impacted, for example, by a perception that the design of the CBDC does not adequately address privacy concerns, that there are insufficient legal safeguards for privacy and autonomous control of personal finances and transactions, and that the use of features such as programmability may violate an individual’s autonomy over their own finances. Again, the Bank’s choice of certain design pathways (preserving privacy to the extent that it is preserved in the existing accounts and payments systems, and introducing a non-programmable CBDC) are aimed at mitigating these.

- There is also a cost associated with adopting new forms of money and payments systems, on the part of businesses and consumers. This is largely unavoidable, and uptake would ultimately be driven by the perceived value and utility associated with a CBDC and the payments functionality that it enables.

The DPF envisages a future in which multiple different forms of money – both public and private, and both those currently in use as well as new forms of digital money – coexist. Each has the potential to fill a different niche in the ecosystem and to provide enhanced consumer and business choices, arising from their different characteristics, the technical functionality that they offer, the nature of their issuers and the risk (both real and perceived) attached to them as a consequence of all of these taken together. In order for our vision of a diverse, competitive and effective ecosystem for new forms of digital money to become a reality, seamless interoperability, convertibility, and – above all else – preservation of the singleness of a digital Pound in all its varied formats, will be required. Just as bank deposits can today be converted into cash, or e-money into bank deposits, the future evolution of money and payments will require equally seamless, trusted and invisible conversion between cash, bank deposits, e-money and new forms of public and private digital money.

2. Do you have comments on our proposition for the roles and responsibilities of private sector digital wallets as set out in the platform model? Do you agree that private sector digital wallet providers should not hold end users’ funds directly on their balance sheets?

The DPF broadly agrees that the platform model as proposed by the Bank of England represents a good division of operational roles and responsibilities between the public and private sectors, in terms of providing the market infrastructure and services that are necessary for the successful introduction of a retail CBDC. Furthermore, the provision of public infrastructure on which private sector firms can develop products and services can incentivise competition and innovation in this space.

As a retail CBDC is introduced, we would expect a diverse range of firms to be able to comply with the regulatory requirements and operational standards associated with PIPs and wallet providers, leading to a diverse, competitive and innovative commercial market.

Privacy is a topic of vital importance, and must be addressed at an early stage if the public is to have trust in a CBDC. The Bank should not look to ‘cut and paste’ today’s regulations and industry best practices with respect to identity verification, but should instead consider from first principles which elements of data should be collected and shared with which parties and for which types of purposes.

In the retail CBDC design envisaged by the Bank, private sector digital wallet providers will not be liable for end users’ funds. With respect to the digital wallet provider’s responsibilities around identity, the wallet provider essentially offers its customer a safe and secure digital deposit box. The eligibility of a person to own retail CBDC is not its commercial interest. Ideally, its regulatory interests should align. Emerging standards for Verifiable Credentials, which we expect to be addressed in subsequent iterations of the Digital Identity and Attributes Trust Framework, will enable a person to establish eligibility from an independent entity and hold the Verifiable Credentials within the digital wallet.

We are particularly heartened by the fact that private sector digital wallet provision will not be restricted to commercial banks, but will rather be opened up to a range of market participants (subject to appropriate regulatory requirements and oversight being introduced). The various business models, opportunities, products and service offerings that may emerge with respect to PIPs remains very much an unknown, and commercial banks may not be best placed – or indeed best incentivised, given the direct impact to credit creation that CBDC outflows may present – to offer these services in a competitive manner, at scale whilst leveraging the full innovative potential on offer.

We absolutely agree that private sector digital wallet providers should not hold end users’ CBDC funds directly on their own balance sheet. There is also an analogy to be drawn to the position of the commercial banks that participate in the Wholesale Cash Distribution process with the Bank. The entire objective of a CBDC is that it should be a form of public money representing a direct claim on the central bank. Should an intermediary hold the CBDC in trust or as a deposit on its own balance sheet, the CBDC would become a liability against the intermediary as opposed to the central bank, thus defeating the objective. It would also create potential confusion between forms of private money such as commercial bank money and e-money, and CBDC as public money. Finally, there is a risk that such models would merely replicate the way in which bank deposits work at present, as a lever for credit creation.

Concerns around an account-centred model

As per above, the DPF is broadly in agreement with the proposed platform model – and in particular the concept that the public sector should have a clear and defined mandate to do only those things that are within its recognised remit, with the private sector then driving innovation (although perhaps not solely responsible for managing and guiding such innovation). This approach will likely result in the most resource- and cost-efficient allocation of roles and responsibilities, as well as the most end-user-friendly outcome, if it is driven by commercial demand and imperatives.

Nevertheless, some of our members are also mindful that the proposed model, without further clarification, may be overly prescriptive, with all transactions ultimately undertaken via a centralised infrastructure, and that this may lead to potentially perverse outcomes. Specifically, these members are concerned that the primary proposal appears to indicate a CBDC model that is primarily account-based – and difficult to distinguish from a centralised (if sophisticated and very large-scale) database. Furthermore, a centralised model of this nature would not be capable of leveraging the benefits and innovative potential of distributed ledger technology and the well-documented innovative leaps that have been made in the traditional financial services sector with respect to digital assets and tokenisation in recent years[3].

A proposed alternative design might take the form of non-custodial wallets, provided by a regulated PIP, holding retail CBDC tokens that are issued by the Bank. This would not only eliminate financial risk to the intermediary (and any concept that the intermediary might hold end user CBDC funds on their own balance sheet) but also, if designed appropriately, could enable the end-user to interact with a broader digital asset and smart contract ecosystem, including private, programmable stablecoins or NFTs, for example, as these technologies become more commonplace and mainstream across the digital economy.

Ensuring successful adoption through a viable retail CBDC ecosystem

The launch of a CBDC will require the creation of a multi-party ecosystem comprising both CBDC service providers and end-users (e.g. businesses and consumers). The CBDC ecosystem will ultimately compete for market share against well established ecosystems like card networks and account-to-account payments networks. A successful ecosystem, in our view, will exhibit two key features:

- Innovation must be a shared responsibility between the ecosystem owner and the ecosystem partners.

- Joining the ecosystem must be underpinned by the ability of participants to extract value from participation.

On the first point, the CBDC ecosystem may require the Bank of England to play a bigger role in innovation. Successful ecosystems have in common the ecosystem owner being the one responsible to develop the first value added services built on top of the platform. For example, before the Apple ecosystem was open to 3rd party developers, it was Apple that developed the iPhone apps. Once the iPhone gathered a critical mass of customers, Apple could attract 3rd party developers. Ecosystems, like that of the iPhone, are characterised by ‘network effects’ whereby the intrinsic value of the ecosystem grows as the number of participants increase.

At the point at which the CBDC is introduced, the ‘network effects’ will be low, due to an initially small number of customers using the CBDC, and an initially small number of merchants accepting the CBDC. Government can also proactively help to create network effects by accepting the CBDC as a means of payment and / or disbursement of funds (for example on taxes, pensions, benefits, etc). Once the CBDC attracts a critical mass of customers, the value of the ecosystem grows as the network effects multiply, and other participants (e.g. merchants and payment interface providers) will have greater incentives to join the ecosystem, thereby increasing the value of the ecosystem as a whole. In addition to developing the first value-added services, the ecosystem owners should work closely with the ecosystem partners to ensure that the platform’s core features are aligned to the value-added services built by the ecosystem partners.

On the second point, the Bank of England, as ecosystem owner, might have a central role in designing a revenue model across the CBDC ecosystem. A UK CBDC, when introduced, will likely compete – at least to some extent and depending on the quality and appeal of PIP services offered – for customers against established means of payment, such as card payments and account-to-account payments. It is common practice in the UK that payments are free of charge for the customer. The competition from free-of-charge payments, will likely prevent PIPs from charging customers for processing CBDC payments, thus also limiting the extent to which PIPs may be incentivised to offer services. A lack of direct revenue opportunities for retail payment interface providers may present a significant barrier to adoption, which in turn may result in the CBDC not reaching an optimal level of end-customer uptake that would enable it to demonstrate benefits. Card networks have solved this problem by introducing a revenue sharing mechanism, that splits the merchant charges between the acquirer bank and the issuer bank.

We can also perhaps draw a comparison with cash, as the current form of publicly-issued central bank money available to the general public. On the withdrawal side, some ATMs are free and others are fee-charging; on the acceptance side, some smaller retailers still prefer cash given that this saves them card handling fees (albeit with handling effort required to deal with the cash). One of our members provided an example of a recent US holiday, at which they saw many petrol stations offering two prices: one for cash and one for card, and some restaurants offering up to a 6% discount for paying in cash. In this example, these businesses are actively beginning to price in the cost of card handling fees and passing these on to their clients. A retail CBDC could enable retailers to lower their overheads when accepting digital payments. A fine (competitive) balance would need to be achieved between any fees charged against existing payment mechanisms.

However, as with the precedent of Open Banking services (e.g. account information services, payment initiation services, etc.), PIPs may be able to generate revenue through additional value-add services (such as subscription fees for features such as automated sweeps, spend analytics, etc.). Firms could also use CBDC wallets as a channel to attract deposits or investments, touting the features of their wallets and then attracting transfers from CBDC into interest-bearing deposits, investment holdings, etc., perhaps on a dynamic/automated basis with user consent. Noting the Bank’s expectation that non-financial firms might also seek to become PIPs, retailers may use this technology as a better way to understand their share of a user’s wallet, redirect users to preferred payment methods, or find value in other ways.

The potential combined effect of a lack of differentiation vis-a-vis competing means of payment and the lack of a clear business case for key ecosystem participants (i.e. retail PIPs) could result in an ecosystem that may ultimately fail to drive adoption on the part of both end-users and service providers. Something to clearly consider as part of the design.

That said, we must emphasise the crucial importance of a regulatory and legal framework around the authorisation, oversight and obligations of PIPs and wallet providers, particularly in terms of ensuring the “singleness” of and convertibility between all forms of the pound Sterling. End users should have certainty of their ability to convert, on demand and at par, between privately-issued commercial bank money / e-money / other (regulated) stablecoin representations of the Pound and CBDC / cash, and this must be supported by the necessary technical interoperability and rails between these different forms of money.

3. Do you agree that the Bank should not have access to users’ personal data, but instead see anonymised transaction data and aggregated system-wide data for the running of the core ledger? What views do you have on a privacy-enhancing digital pound?

The DPF is strongly supportive of a privacy-enhancing retail CBDC; that said, any new form of digital money should be designed such that some of the main types of crime that are plaguing the existing payment networks are reduced, if not eliminated. We agree that public trust in the retail CBDC is of utmost importance in ensuring successful adoption, and applaud the Bank for recognising this and for prioritising it as a design consideration accordingly. The central bank, as an issuer, is in a unique position in comparison with the private sector, in that it does not have a commercial incentive to collect or monetise individual transaction data. Similarly, whilst the government might have an incentive to identify or monitor individual transactions for taxation purposes or for benefits management, for example, the Bank’s narrow remit and focus on delivering monetary and financial stability policy leaves it well-placed to advocate for and to implement a privacy-enhancing retail CBDC. The time and investment spent in developing a privacy-enhancing retail CBDC could be perceived as a public good for the broader economy, as well as an opportunity for leadership on the global stage.

We imagine that the role of the Bank of England will not change in the course of introducing a CBDC. It should therefore aim to have access to the data needed for managing monetary policy and financial stability. We do not believe this requires the Bank to have access to users’ personal data. It should be noted, however, that many members of the public end-user population may not be comfortable with the Bank having access to or being able to view even anonymised transaction data and wallet holdings, given the potential that they might be subject to additional surveillance and scrutiny.

In the short term, the existence of holding limits may also help to mitigate some of these concerns, as the existence of millions of anonymised wallets holding relatively low balances would not likely be perceived as a likely vector for large-scale criminal activity, and so would be subject to correspondingly lower levels of scrutiny. Similarly, a CBDC that lacks programmability (whilst this may have downsides) does have clear benefits in terms of public trust in their control over their money and transactions.

However, money laundering and financial crime are a growing problem – globally estimated at costing between 3 and 5% of GDP. As payment innovations develop, financial crime evolves alongside them; recently the PSR announced requirements for mandatory reimbursement from banks and payment firms with respect to authorised push payment (APP) scams. A retail CBDC must not make it any easier for any crime to take place, and ideally, should actively prevent fraud, crime or AML layering. The Bank should take this opportunity to consider why current regulations, initiated in the 1980s and incrementally revised at great cost to all parties, have been so ineffective in addressing these issues.

Today, individual financial institutions are responsible for preventing financial crime. There is no overarching governance body with responsibility for policing the unlawful use of payments systems and, as the Bank has set out in the Consultation, data protection law inhibits sharing of data between institutions. However, without sight of the end-to-end flows of payments, it is very difficult for an individual financial institution to detect suspicious patterns. The result is a costly requirement and process for financial institutions, and a poor customer experience for users.

It is important for all that the system for the CBDC should be able to identify and police misuse of the payments infrastructure without posing a risk – whether real or even merely perceived – to civil liberties and personal privacy. Technological solutions are available that can enhance privacy safeguards when people transact. However, these solutions require the rethinking of the roles and responsibilities of the various stakeholders involved in the ecosystem surrounding a CBDC, and the data to which they will require access in order to perform those roles effectively.

A new entity is potentially required, with distinct and separate governance, to oversee the safeguarding of the CBDC from misuse by criminals. The DPF’s Identity and Privacy Working Group is currently considering this subject and would happily share its outputs with the Bank as they are developed.

The Bank’s ability to access unique identifiers also feeds into the solutions to certain of the notions covered in the Consultation, for example the functioning of the limit on CBDC holdings. Without a centralised view of unique holders of the CBDC, creative solutions will be required to police the limit, in a scenario in which user identity is known only to the PIP(s) who onboard(s) them. An alternative would be a self-certification regime akin to that for ISAs, but this is unlikely to be as effective for a retail CBDC without the tax fraud deterrent, adverse tax consequences more generally, and abuse of the limits still not increasing the credit risks faced by dishonest users. However, if the limit’s main purpose is to minimise disintermediation, then the FSCS, interest rates on commercial money and honesty among the general populace should achieve most of that policy goal while preserving privacy and managing development cost.

4. What are your views on the provision and utility of tiered access to the digital pound that is linked to user identity information?

The Bank envisages in the Consultation, that tiered access to services and products around a retail CBDC could allow for different levels of user access and functionality depending on the level of identification and personal data that a user is willing or able to provide. The DPF agrees that, as part of a privacy-enhancing retail CBDC design, tiered access can not only empower individual end-users to make informed decisions about their transaction data, but also allow for the offering of entry-level services to a user base that may traditionally be excluded from the financial system due to a lack of adequate documentation.

Commercial advantages of a tiered access model

From a commercial perspective, a tiered access model could be very attractive to would-be PIPs, enabling PIPs / wallet providers to offer a competitive range of products and services to end-users whilst realising commercial benefit through the ability to monetise consumer data where this is actively permitted by the end-user. This could also open up opportunities for a range of non-bank PIPs to offer services around a retail CBDC, and the prospect of cheaper – or enhanced – wallet services for those that are willing to share more data and to specify how that data might be used.

Nevertheless, we are also mindful that this may be an idealised outcome, and there is a genuine risk that some types of firms – based on historical experiences with data collection and sharing via cookies, or complex and difficult to understand End User Licence Agreements (EULAs) – may attempt to obfuscate the true extent and intended use of the data that they collect. In this scenario, choice may be an illusion, and end-users may in fact have little choice but to accept unfavourable and undesirable terms around data collection and usage in exchange for services.

It could also result in an outcome whereby those who are either excluded from existing financial services, or on lower incomes, may be unable to control their privacy and identity to the same extent that other end-users might be able to. Conversely, there is also a need to ensure that the “lowest” tiers of users are not more susceptible to being targeted for financial crime or scam purposes. We are also very strongly of the view that the introduction of a tiered access retail CBDC should not become a platform for creating products and services that target lower income groups and vulnerable individuals, as we have seen happen with Buy Now Pay Later and payday lending. A tiered access system based on varying levels of individual identity data disclosure will therefore require careful regulation and supervision on the part of the Financial Conduct Authority, a high standard of consumer protection that is proportionate to the risk of data misuse, and clear disincentives to the misuse of data.

Tiered access and potential for fraud

Fraud vectors change over time. Electronic payments have replaced the movement of cash and cheques over time (initially for high value payments although the trend has been to ever-smaller payments). Customer demand for contactless payments is now driving out cash usage even for the smallest payment amounts. This trend is likely to continue and the introduction of the CBDC, with its close coupling of identity data and payment mechanisms, may facilitate innovations in micropayments where, for example, a person can conveniently access information on a ‘pay-per-page’ basis.

However, it is also likely that fraudsters will seek to exploit future ‘regulatory arbitrage’ opportunities. Whatever threshold is set, technology may allow fraudsters to cost-effectively split large payments into smaller and smaller amounts in order to fall below the threshold. These techniques are already employed in cryptocurrencies so there’s no reason to think the same would not be attempted in CBDC. This is a risk that must be considered as well when introducing any tiered approach to identity verification.

Proving one’s identity should not be complex. Over time, we expect the introduction of the Digital Identity and Attributes Trust Framework to make it easier and more commonplace for people to assert highly trustworthy identity details through digital means. Inclusion is a key objective: the use of a bus pass or driving licence as the only available form of identification will diminish quite rapidly.

We should also distinguish between the process of enrollment and that of transactional authentication. During enrolment, a person establishes an identity and, in this context, their eligibility or suitability to open a given type of digital Pound account. Subsequently, the method of authenticating that the transaction is being conducted by the right person would require an appropriate level of security, depending upon the risks.

5. What views do you have on the embedding of privacy-enhancing techniques to give users more control of the level of privacy that they can ascribe to their personal transactions data?

We are supportive of measures that can provide end-users with greater control over the level of privacy that they can ascribe to their personal transaction data, provided that this is balanced with the need to ensure that a retail CBDC is not used as a conduit for proceeds of crime. Such measures, if they are to engender the greatest level of public trust and confidence, should be embedded in the technology by design and within the core publicly-run infrastructure. Notwithstanding this, we also acknowledge that it will be necessary for the Bank and the CBDC ecosystem participants to be able to access data on an anonymised or aggregated basis, not only with respect to prevention and detection of financial crime activities but also in order to monitor usage of the CBDC across the economy and as a means of designing and developing end-user products and services.

As the Bank has observed, privacy is a relative term. It is not possible to transact without an exchange of information. The more information that a person is prepared to share, the greater potential for value in the transaction. However, many firms are able to recognise and (profitably) exploit the power of personal data because its value is not always apparent to the person to whom it belongs.

Privacy enhancing techniques offer many exciting opportunities to provide people with greater control over their personal data. However, it is not the individual that makes the data ‘trustworthy’ to a third party. Open Banking has indeed been successful but that is because highly valuable bank curated data has been opened to the market for free.

Security and the creation of trustworthiness are costly. People in their daily lives seldom consider their value until a fraud vector makes them vulnerable. This allows some organisations to exploit data that is exposed to them and that they are able to aggregate.

We should not begin by discussing how one technology or another is used. Instead we should consider the roles required and which personal data are required to fulfil those roles effectively. For example, if determination of eligibility to open a CBDC account were delegated to a government certified third party organisation (such as that envisaged under the government’s Digital Identity and Attributes Trust Framework) then the PIP need be responsible for authentication only i.e. providing assurance to customers that their money is safe.

Even without the ‘real world’ identity of the account holder being known, there are arguments for and against the tracking of transactions by a PIP. Having established what a PIP can and cannot do with the personal data to which it is exposed, it is then possible to consider how privacy-enhancing techniques can or should be used. But the regulatory framework – not technology – should be relied on in the first instance to protect data privacy rights (although this does not preclude the inclusion of ‘privacy by design’ as a consideration in the technical architecture and market structure of a retail CBDC).

The DPF’s Identity and Privacy Working Group will be undertaking a review of existing Privacy by Design principles in the context of the Bank’s proposals for a retail CBDC digital Pound, and expects to publish this in due course.

6. Do you have comments on our proposal that in-store, online and person-to-person payments should be highest priority payments in scope? Are any other payments in scope which need further work?

The DPF agrees that in-store, online and person-to-person payments should be the highest priority payments in scope. In addition, we recommend that government payments should be in the highest priority from day one.

If the Bank’s intention is, at this stage, to create a CBDC that will primarily be used for retail payments, then it makes logical sense to prioritise in-store, online and person-to-person payments. That said, if retail CBDC payments are being made to businesses then either a mechanism should be devised such that all CBDC payments are swept to commercial bank accounts on receipt, or businesses should be allowed to use their retail CBDC holdings as a store of value as well as a means of payment. The Bank has also made reference to employee salaries being paid in retail CBDC; these funds would presumably need to come from their employers’ CBDC accounts.

The extent to which such payments and their supporting applications will be successful has a significant dependence on their ease of use by the end-user, and the additional utility / benefit they are perceived as offering over and above that of other payment mechanisms. A system that introduces more friction than existing forms of in-store, online or person-to-person payments – or one that does not align with the possibilities offered by initiatives such as Open Banking – will be unlikely to experience sufficient uptake. The user experience in terms of the level of seamless conversion and interoperability between existing forms of money and payments, and future systems, will also be key.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS)[4] has analysed the three factors that might make adoption of a retail CBDC, such as the digital Pound CBDC, a success. The conclusion is based on previous implementations of payment innovations, and includes the following criteria that a given retail CBDC must, in order to be successful, deliver the following:

- fulfils unmet user needs; and

- achieves network effects; and

- does not require users to buy new devices.

In-store and online payments are a hygiene factor in terms of adoption. They are required if the CBDC is to provide basic convenience, without which customers would be unlikely to consider adopting it as a payment method. Every payment innovation faces a ‘chicken-and-egg problem’ whereby merchants are not incentivised to adopt the payment innovation unless there are customers using it, yet conversely customers lack an incentive to use it unless there are merchants accepting it. Person-to-person / peer-to-peer payments are an important mitigant in the ‘chicken-and-egg problem’ with respect to merchants and customers, helping to build the critical mass on the customer side, so that merchants see clear commercial benefit in joining the ecosystem.

Government payments are important to the establishment of a successful digital Pound CBDC ecosystem from two angles:

- Firstly, adoption of the CBDC by the UK Government, for its own payment and disbursement requirements, would bring additional credibility to the CBDC, thereby creating a sense of trust and confidence underpinning the adoption of a new form of digital money.

- Secondly, given the scale of users / ‘customers’ to which it has reach, adoption on the part of the UK Government could contribute significantly towards building the network effects of the CBDC, thereby breaking the ‘chicken-and-egg problem’ between the merchants and customers.

If history can be a guide for the future, two mainstream payment innovations, contactless and Open Banking, have had public sector firms as successful early live use cases. It was Transport for London that enabled contactless payments to enter onto a path of widespread adoption. Transport for London became such a symbol for the success of payment innovations that it became common to define the quest for the identification of a key use case for a payment innovation as finding ‘the TfL moment’. Similarly, HMRC has become a flagship[5] use case driving customer trust in Open Banking payments.

Additionally, there is another payment use case that could potentially be in the highest priority. This payment use case would have the objective to ‘fulfil unmet user needs’. The UK is currently lacking in a service that can enable the delivery of requests for payment in a secure channel like home banking or a banking app. In reality, such a service has been created – in the form of ‘Request to Pay’[6]; however, it is not yet provided by any bank and is not yet in use by any business. The key reasons for the failed adoption of Request to Pay include a ‘lack of business case for retail banks’ and the ‘chicken-and-egg adoption problem’. Notwithstanding this, the market itself has arguably brought a variation on this capability before the scheme, with several challenger banks including Starling, Monzo and Revolut offering a pay request feature both within their ecosystem (P2P) and as a card payment option; additionally, companies such as Comma have introduced Open Banking options for payment requests. These offerings do prove that there is a market for Request-To-Pay-like services.

In Australia[7] and Switzerland[8], Request-to-Pay-like services have achieved relative success, empirically proving that there is a market need and appetite for this service. In these two jurisdictions, the service was a market solution, meaning that the banks were not mandated to implement it as a regulatory initiative such as Open Banking in the UK. Their success may be ascribed to the role of the payment companies behind the schemes in creating the ecosystem and realising the network effects. In Switzerland, the Request-to-Pay infrastructure existed for some years prior to SIX Group merging two different Request-to-Pay ecosystems and thus building a larger and more solid base for network effects. In Australia, the BPAY company was successful in convincing banks and large utilities to join the ecosystem from the beginning[9], thereby realising the network effects from the start. The ability of a CBDC to support Request-to-Pay-like services could help to differentiate the CBDC – in the minds of consumers – from bank deposits, thereby helping to attract customer adoption.

7. What do you consider to be the appropriate level of limits on individual’s holdings in transition? Do you agree with our proposed limits within the £10,000–£20,000 range? Do you have views on the benefits and risks of a lower limit, such as £5,000?

The Bank of England has clearly stated its reasons for introducing limits on individual holdings of a CBDC within the Consultation; namely, to mitigate the risks of bank disintermediation (and hence any potential impact on credit creation) in the course of introducing a CBDC, and to create a window for gathering data on user behaviour, and understanding the demand for a CBDC and its potential impact on the wider economy. The DPF is supportive of this proposed approach when rolling out a CBDC, and we are of the view that the higher limit of £20,000 would better support the Bank’s learning objectives during a transitional period. We think that a lower limit, such as £5000, may deter some users from making full use of a CBDC and would be unhelpful in achieving the aim of understanding the impact of a retail CBDC on consumer behaviour, financial institutions and the economy.

Some of our members expressed concern that a £20k limit might actually be too low, giving the example of NS&I premium bond holdings, for which the limit is £50k per individual. There are no similar concerns raised at the prospect of disintermediation of bank and building society savings accounts as a consequence of this. On the other hand, NS&I is a savings product, and so faces a different set of trade-offs to a retail CBDC which would be primarily intended as a transactional product, and if NS&I were a new product that was introduced today, the macroprudential regulator would probably want to phase it in gradually to manage any potential impact on financial stability.

It can also be argued that most individuals in the UK do not have savings levels that would cause the levels of disintermediation that are envisaged with respect to the introduction of a retail CBDC. Others observed that a digital-native retail CBDC, with effectively zero cost to acquire, does potentially lead to the risk of accumulation by speculators and a potential break of parity (and the “singleness” of the pound Sterling across its different forms).

Members proposed consideration of alternative solutions that might equally or better address the same risk, such as:

- The introduction of overall limits to retail CBDC issuance, similar to those used for notes and coins in circulation.

- Disincentivising higher holdings with a charge on holdings above a certain limit (i.e. a form of negative interest rate, similar to what commercial banks have done to EUR and JPY business deposits above a certain amount during negative interest environments).

However, having a vector such as a retail CBDC might increase the ease – and therefore risk – of large-scale runs when there is next a more general loss of trust in the banking system. Whilst lining up at a bank or ATM to withdraw cash has intrinsically limited throughput, and can provide more time for the bank and its supervisors to find an orderly solution, recent banking crises have been accelerated by customers’ ability to transfer their balances to “safer” banks at the touch of a button. During a more systemic event, a no-limit CBDC could make it easier and more likely for large-scale, high-velocity withdrawals of funds from the banking system to occur. Conversely, this systemic loss of trust is something that the current deposit guarantee schemes have been designed to address, and for which purpose they so far appear to remain a useful tool.

Perhaps more pertinently, the bank deposits and e-money holdings of individual consumers are guaranteed to the level of £85,000 through the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS), enhancing trust in the current commercial banking system.

Guaranteed deposits and physical cash are probably more accessible to most members of the general public than are gilts. It is worth noting, however, that the availability of such relatively low-risk assets has not been shown to create, or to exacerbate in such a way that the Bank is not confident of being able to mitigate, financial instability in the banking sector, nor has it led to any disintermediation of commercial banks. A future area for navigation may involve the education of customers about there not being any real need to move (large) deposits below the FSCS limit into CBDC. (We qualify “large” in this way to give some spending runway while the FSCS pays out – some small CBDC holding may still make sense for that reason.)

We are also mindful that the introduction of limits may have a critical role to play in the viability of the early CBDC ecosystem, and this should also be a guiding principle in any consideration or discussion of limits. Whilst limits might not ultimately be the most necessary or effective means of preventing and managing financial instability, the existence of limits may be a crucial vector in obtaining support from financial institutions and banks for a retail CBDC.